Concealed within the desolate, rocky, landscape of the Makran coastline of Southern Balochistan, Pakistan, is an architectural gem that has gone unnoticed and unexplored for centuries. The Balochistan Sphinx, as it is popularly called, came into the public eye only after the Makran Coastal Highway opened in 2004, linking Karachi with the port town of Gwadar on the Makran coast. A four-hour long drive (240 kms) from Karachi, through meandering mountain passes and arid valleys, brings one to the Hingol National Park where the sphinx is located.

The Balochistan Sphinx

The Balochistan Sphinx is routinely passed off by journalists as a natural formation, although no archaeological survey appears to have been conducted on the site. If we explore the features of the sphinx, as well as some of the associated structures, it becomes very difficult to accept the oft-repeated premise that it has been shaped by natural forces. Rather, the entire site looks like a gigantic, rock-cut, architectural complex.

A cursory glance at the impressive sculpture shows that the sphinx has a well-defined jawline, and clearly discernible facial features such as the eyes, nose, and the mouth, which are placed in perfect proportion to each other.

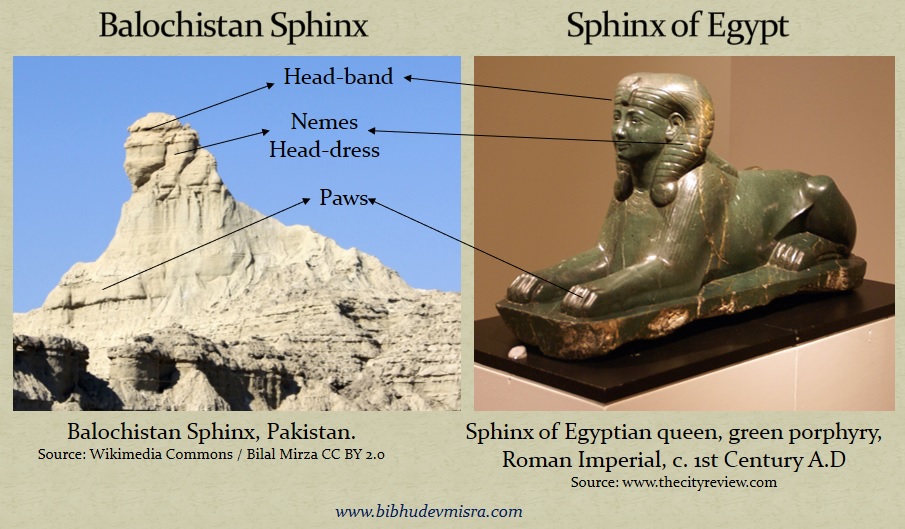

The sphinx appears to be decked up in a head-dress that closely resembles the Nemes head-dress of the Egyptian pharaoh. The Nemes head-dress is a striped headcloth that covers the crown and back of the head. It has two large, conspicuous, flaps which hangs down behind the ears and in front of both shoulders. The ear-flaps can be clearly seen on the Balochistan sphinx (including some stripe marks on it as well). The sphinx has a horizontal groove across the forehead which corresponds to the pharaonic head-band that holds the Nemes head-dress in place.

One can easily make out the contours of the reclining forelegs of the sphinx, which terminate in very well-defined paws. It is ridiculous to suggest that nature has carved out a statue which resembles a well-known mythical animal to such an extraordinarily high degree.

In Indian art and sculpture the sphinx is known as purusha-mriga (meaning man-beast in Sanskrit). It appears in the early Hindu-Buddhist art of Central and North-west India from the 1st century BCE onwards, and was incorporated into the artistic motifs of South Indian Temples by the Pallavas and the Cholas from around the 6th century AD.

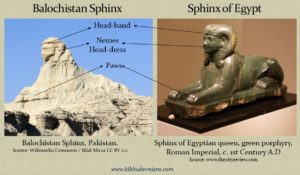

The extensive research done on this subject by Raja Deekshithar indicates that, the primary position of the Indian sphinx was near the temple gateway, acting as a guardian of the sanctuary. This is a common motif in sacred architecture, where a pair of sphinx may be placed on either side of the entrance to a temple or sacred monument. In Indian art, it was also carved inside the Mandapas (halls) and the Garba-griha (shrine room). It appears in a variety of poses: in a crouching form, in a striding or jumping form, in a half-upright form engaged in the worship of a Shiva-Linga etc.[1] In one of its forms it crouches or stands in front of a miniaturized temple.

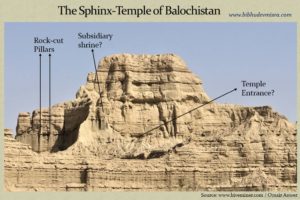

The Balochistan Sphinx-Temple

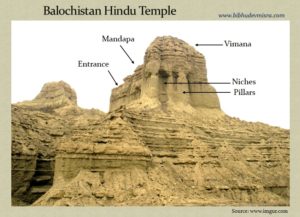

Very close to the sphinx is another important structure. From a distance, it looks like a Hindu Temple (like those of South India) with the Mandapa(entrance hall) and the Vimana (temple spire). The top part of the Vimana appears to be missing. The sphinx is reclining in front of the temple, acting as a guardian of the deity embodied in the shrine.

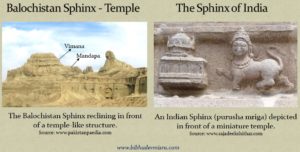

On closer inspection, it seems that the Sphinx-Temple may be the Gopurami.e. entrance tower of a temple. Like the Sphinx-Temple, gopurams are generally flat-topped. Gopurams have a row of ornamental kalasams (stone or metal pots) arranged on the top. If we look carefully at the flat-topped Sphinx-Temple we can see a number of “spikes” on top, which could be a row of kalasams, covered with sediments or termite mounds.

Gopurams are attached to the boundary wall of a temple, and the Sphinx-Temple appears to be contiguous with the outer boundary. An elevated structure to the left could be another gopuram.

This implies there might be four gopurams in the cardinal directions leading to a central courtyard, where the main shrine of the temple complex was built. The central shrine cannot be seen in this image. The Sphinx is facing the temple complex, possibly towards the gopuram facing east.

The Sphinx-Temple shows clear evidence of pillars carved on the boundary wall. The temple entrance is visible behind a large pile-up of sediments or termite mounds. An elevated, sculpted, structure to the left of the entrance could be a subsidiary shrine. Overall, there is little doubt that this a massive, man-made, rock-cut, temple of immense age.

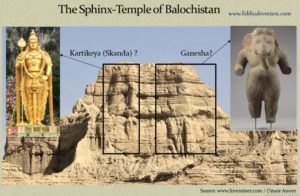

Very interestingly, there are two massive sculptures carved on the façade of the Sphinx-Temple, right above the entrance, on either side. They are heavily eroded, but it looks like the figure on the left could be Kartikeya (Skanda / Murugan) holding his spear (vel), while the figure on the right could be a striding Ganesha.

Gopurams generally have figures of a pair of dvarapalas carved on either side of the entrance, and these two figures might be serving as dvarapalas. If the figures are those of Skanda and Ganesha, then it is possible that the main shrine was dedicated to Shiva, for Kartikeya and Ganesha are both sons of Shiva.

Both the sphinx and the temple are covered by layers of sediments or termite mounds, masking the more intricate details of the sculpture. We must remember that the Makran coast of Balochistan is a seismically active zone, which frequently produces enormous tsunamis that rush on to the land, obliterating entire villages. It is reported that the earthquake of November 28, 1945, with its epicenter off the coast of Makran, caused a tsunami with waves reaching as high as 13m at some places.

In addition, a number of mud volcanoes are strewn along the Makran coastline, with a bunch of them concentrated within the Hingol National Park, near the delta of the Hingol river. Intense earthquake activity triggers the mud volcanoes to erupt, which can spew staggering amounts of mud drowning the surrounding landscape. Sometimes, mud volcano islands appear in the Arabian Sea, off the coast of Makran, which are dissipated by wave action within a year.

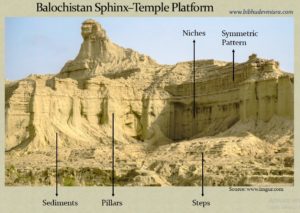

The Sphinx-Temple Platform

The elevated platform on which the sphinx and the temple are situated, also appears to have been elaborately carved with pillars, niches, and symmetric patterns – in the manner of the later rock-cut temples of India. Some of the niches may be doors which lead to chambers and halls under the Sphinx-Temple complex. It is believed by many that there are chambers and passages under the Sphinx on the Giza plateau as well – a belief which is supported by an extensive study conducted by a Japanese team within the Sanctuary of the Sphinx. It is also interesting to note that the Balochistan Sphinx and Temple are situated on an elevated platform, just as the Sphinx and the Pyramids of Egypt were built on the Giza plateau overlooking the city.

Another conspicuous feature of this site is a series of steps, covered by layers of sediments, leading to the elevated platform. The manner in which the steps have been cut out – they appear to be evenly spaced and of uniform height – rules out nature as a potential cause. The entire site gives the impression of a grand, rock-cut, architectural complex, which has been eroded by the elements, and covered with sediments and termite mounds.

The Historical Context

It should not come as a surprise to find an elaborate Indian temple complex on the Makran coast, for Makran had always been regarded by the Arab chroniclers as the “frontier of al-Hind”. Even though the sovereignty of parts of the region alternated between Indian and Persian kings from very early times, yet it was regarded as distinctly Indian territory by most writers of antiquity. In the decades preceding the Muslim raids, Makran was under the dominion of a dynasty of Hindu kings, who had their capital at Alor in Sind.[2]

When the Chinese pilgrim Hiuen Tsang visited Makran in the 7th century AD, he noted the script which was in use in Makran to be “much the same as India”, but the spoken language “differed a little from that of India”. Historian Andre Wink writes that:

“The same chiefdom of Armadil is referred to by Hiuen Tsang as O-tien-p’o-chi-lo’, located at the high road running through Makran, and he also describes it as predominantly Buddhist, thinly populated though it was, it had no less than 80 Buddhist convents with about 5000 monks. In effect at eighteen km north west of Las Bela at Gandakahar, near the ruins of an ancient town are the caves of Gondrani, and as their constructions show these caves were undoubtedly Buddhist. Traveling through the Kij valley further west (then under the government of Persia) Hiuen Tsang saw some 100 Buddhist monasteries and 6000 priests. He also saw several hundred Deva temples in this part of Makran, and in the town of Su-nu li-chi-shi-fa-lo – which is probably Qasrqand- he saw a temple of Maheshvara Deva, richly adorned and sculptured. There is thus very wide extension of Indian cultural forms in Makran in the seventh century, even in the period when it fell under Persian sovereignty. By comparison in more recent times the last place of Hindu pilgrimage in Makran was Hinglaj, 256 km west of present day Karachi in Las Bela.”[3]

Thus, as per the accounts of Hiuen Tsang, even in the 7th century AD, the Makran coast was dotted with hundreds of Buddhist monasteries and caves, as well as several hundred Hindu Temples, including a richly sculpted temple of Lord Shiva. What happened to these caves, temples, and monasteries of the Makran coast? Why have they not been restored and brought into the public eye? Are they suffering the same fate as the Sphinx-Temple complex? Most certainly so. Eroded by the elements and covered with sediments these ancient monuments have either been entirely forgotten or are being passed off as natural formations.

As an example, very close to the Balochistan sphinx, on top of an elevated platform, we can see the remnants of what clearly appears to be an ancient Hindu temple, complete with the Mandapa, Shikhara (Vimana), pillars, and niches.

The question is, how old are these temples of Makran? We must remember that the Indus Valley civilization extended along the Makran coastline, the westernmost archaeological site being Sutkagen Dor near the Iranian border. Therefore, some of the Hindu temples and rock-cut sculptures of this region, including the Sphinx-Temple complex, could have been built thousands of years ago, during the Indus Period (c.3000 BCE) or even earlier. It is possible that the entire site was built in phases, with some structures being extremely old, and the others comparatively recent.

Dating of rock-cut monuments, however, is a difficult proposition in the absence of inscriptions. If the site contains readable inscriptions, and if they can be interpreted (another tricky proposition, given that the Indus script has not yet been deciphered) then it may be possible to put a date on some of the monuments. In the absence of inscriptions, scientists will have to rely on datable artifacts / human remains, architectural styles, erosion patterns, and other archaeological clues.

One of the persistent mysteries of the Indian civilization has been the profusion of exquisite rock-cut temples and monuments that were built since the 3rd century BCE. How did the skills and techniques for building these sacred places of worship appear all of a sudden, without a corresponding period of evolution somewhere? The rock-cut monuments of the Makran coastline may provide the much-needed continuity between the architectural forms and techniques of the Indus period and the later-day Indian civilization. It may have been on the mountains of the Makran coast that the Indus artisans honed and perfected their skills, which were later transported to the Indian civilization.

Undoubtedly, there is a virtual treasure trove of archaeological wonders waiting to be discovered on the Makran coast of Balochistan. Unfortunately, these magnificent monuments, whose origins go back to unknown antiquity, continue to languish in isolation, thanks to the appalling level of apathy towards them.

It appears that absolutely no attempt has been made for their restoration, and both the authorities as well as the journalists are only too happy to pass them of as “natural formations”. The situation can only be salvaged if international attention can be drawn to these grand structures, and if teams of archaeologists (as well as enthusiasts) from around the globe visit these enigmatic monuments to research, restore, and publicize them.

The importance of these ancient monuments of the Makran coast can hardly be overstated – they could literally be thousands of years old – and they can potentially provide us with important clues to uncover humanity’s mysterious past.

Source: bibhudevmisra