It’s the first-ever comprehensive profile of prominent Baloch leader, Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti, written by Sajid Hussain.

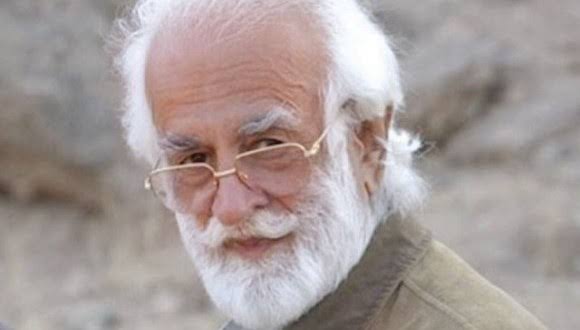

Despite his scandalous politics, Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti is the most talked-about person in Baloch society. With his twirling moustache, keenly trimmed beard, over six-feet-tall stature, candor, bravery, unbending backbone and uncompromising pride, he epitomized a model Baloch character. Ask anyone in Balochistan, they tell you he was the truest Baloch ever, even if they are ignorant of his 60-year-long politics.

Born on July 12, 1927 in Barkhan, he was assassinated on August 26, 2006 in a military raid on the orders of the then military dictator General Pervez Musharraf, who termed it a great military achievement.

His death was followed by days of violent protests and he became the undisputed hero for the Baloch people.

He was the eldest son of Nawab Mehrab Khan Bugti and grandson of Sir Shahbaz Khan Bugti. His father named him Akbar, but, after the incorporation of his grandfather’s name, he was called Nawab Akbar Shahbaz Khan Bugti.

His father died in 1939, and he became the chief of his tribe when he was only 12. Due to his young age, the British Political Agent assigned his half-uncle, who Bugti believed poisoned his father, as the regent and sent him as a ward to famous educationists Allama I.I. Qazi and his German wife Elsa Qazi.

He studied at the Karachi Grammar School and then at the Aitchison College Lahore. He was not allowed to visit Dera Bugti, his hometown, for his safety. He spent his holidays with Qazis.

But he seemed to have enjoyed his time at Aitchison. He excelled in sports: he was the captain of the polo and swimming teams and was good at cricket. He was one of the first CSP officers of Pakistan, but he rather preferred leading his tribesmen than serving as a government official.

At nine or perhaps ten, he was “betrothed to a second cousin, an incident of which he has no memory,” as he told Najma Sadiq, 35 years back in an interview with the Herald magazine.

“Soon after his 15th birthday, the respective mothers and other relatives suddenly turned up in Lahore and Akbar was informed that he was going to be married. It was a quiet affair and in 1943, when only 16, his first child was born. For two consecutive summers he and his brother Ahmed along with the Kazis and their wards, vacationed at a hill-station thirty miles near Simla, his family accompanying too, staying at an adjoining separate house.”

Later he married two more times: once with a Pakhtun woman and then with an Iranian.

Akbar Bugti’s first trip abroad was to attend the crowning ceremony of England’s Queen in 1953. He described the event to Najma Sadiq as: “It was a fine ceremony and I was struck especially by Queen Salote of Tonga; she was seven feet tall and with her huge bulk, she was an impressive figure indeed.”

Despite his modern education, he was a traditional tribal chief. He was five when he shot his first shotgun. “It was a small bore shotgun – not 12 or 16 but 28 bore – one of the smallest. I sat on my haunches and fired. Immediately I was thrown back and the gun fell from my hands,” he told Najma.

But he was not deterred. At the age of 12, he killed his first man.

“Well, the man annoyed me. I’ve forgotten what it was about now, but I shot him dead. I’ve rather a hasty temper you know, but under tribal law of course it wasn’t a capital offence, and, in any case, as the eldest son of the Chieftain I was perfectly entitled to do as I pleased in our own territory. We enjoy absolute sovereignty over our people and they accept this as part of their tradition,” a 21-year-old Bugti told Sylvia Matheson, a British traveler and writer who spent several years in Dera Bugti to research the lifestyle of the Bugti tribesmen. She wrote her experiences in a book, The Tigers of Baluchistan, first published in 1967.

When she asked Bugti about how many men he had killed, he responded he had lost the count.

His long-time friend and the late writer Ardeshir Cowasjee called him “arrogant and handsome”. In September, 2006, Cowasjee wrote for Dawn that when they first met in 1960s in Karachi, Bugti asked him why Cowasjee spelt his name wrongly.

“That I did not react did not please him. He went on to tell me that we silly Parsis did not even know the correct name of their own prophet. He was Zardost and not Zarathustra as many of us ignoramuses were wont to refer to him. He knew all about how the Zoroastrians had fled Iran after the Muslim invasion, fearing for their lives…” Cowasjee wrote.

His knowledge of history was impeccable. An insomniac, who couldn’t sleep at all, he read book after book all night, when everyone else was asleep. He read extensively about English literature, Balochi classical poetry, politics and history. He owned one of the largest private libraries in Pakistan which was destroyed in a 2005 bombing by the military at his Dera Bugti palace, also killing over 60 women and children. A large number of the victims were from the Hindu community who he had allotted lands around his house.

After the videoed aerial bombing that almost killed Bugti, he decided to go to hiding in the mountains. Musharraf blamed him and his tribesmen for bombing military and government installations and launched a full-fledged military operation against him.

Although Bugti never accepted any role in the Baloch armed insurgency that started after 2001, he expressed his support for the Baloch insurgents, saying they were fighting for their due rights.

He was particularly close to Balach Marri, the then head of the Baloch Liberation Army. He said in a televised interview that the military wanted to wipe out him and Balach.

Initially, he claimed he wanted greater autonomy for Balochistan, but as the military operations escalated he said, at least on one occasion, this fight is now for an independent Balochistan.

Despite being among the first few Baloch chieftains to support Balochistan’s amalgamation with Pakistan and supporting Pakistan Muslim League, he had a tumultuous rapport with successive Pakistani governments.

In 1947, he voted in Pakistan’s favour in a Shahi Jirga, which was boycotted by most Baloch politicians, in Quetta.

In 1950, he contested elections for Pakistan’s Constituent Assembly but lost against Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s brother.

In 1958, he was elected as a member of the Assembly in a by-election. He served as Interior Minister of State but his tenure was short-lived as President Iskandar Mirza declared martial law in October the same year and dismissed the cabinet.

Due to his opposition to Ayub Khan, he was arrested for allegedly murdering Haybat Khan, his own uncle. He was sentenced to death by a military court but later Ayub Khan ordered his release, commuting the death sentence.

He told journalist Sohail Waraich in a television programme, aik din Geo ke saath, that he spent eight years in jail.

Bugti mocked Cowasjee for writing an apology letter to the then Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1976 for the latter’s release. Bhutto had shown that letter to Bugti. Cowasjee’s letter to Bhutto read:

“Dear Mr Prime Minister, I believe I have caused you annoyance and if I have, I sincerely apologise. I have been your sincere friend and remain so.”

Bugti went on teasing Cowasjee that he was jailed too but he never sought pardon.

Seasoned Baloch politician Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo managed to unite Bugti, Ataullah Mengal and Khair Bakhsh Marri on National Awami Party’s platform in the political battle against the infamous one-unit, which had merged the four provinces of West Pakistan as a single polity to undermine the majority of East Pakistan (now Bangladesh).

The one-unit programme, established on November 22, 1954, was eventually dismantled in 1970 and Balochistan got provincial status. Elections were held the same year.

Bugti had been banned from holding political office by the military court since 1960, thus he could not contest the elections. But he campaigned on behalf of the NAP, which formed a coalition government in Balochistan.

Bugti’s younger brother, Ahmed Nawaz Bugti, was elected as a member of the first Balochistan Assembly. Ataullah Mengal became the chief minister and Bezenjo the governor. However, their success was short-lived.

Bugti soon developed serious differences with the NAP government. According to him, he was once attending a NAP meeting, and as the meeting was about to start someone shouted “those who are not formal members of the party should leave”. As Bugti was not a formal member, he realized it was him being referred to. He said he tried to ignore the situation. But the man repeated himself, and Bizenjo, who was present, remained silent. It offended Bugti and he left.

When Bhutto dismantled the Balochistan government in 1973, Bugti supported his move to avenge the “disrespect” shown to him by NAP leaders.

Mengal, Marri and Bizenjo were jailed and a military operation was initiated in Balochistan which lasted till 1977.

Bhutto also took advantage of the sore relationship of Bugti with other Baloch leaders. He appointed him as the governor of Balochistan on Feb 15, 1973. But Bugti said he realized he was being used and he developed serious issues with Bhutto, and eventually resigned, nine months after his appointment.

He remained silent during most of Ziaul Haq’s dictatorship. He did not contest the non-party elections in 1985.

He formed the Balochistan National Alliance in 1988 and contested general elections the same year. He was elected as a member of the Balochistan Assembly and eventually the chief minister. He served as the provincial chief till 1990 when the assemblies were dissolved by the federal government.

In August, 1990, he set up the Jamhoori Watan Party. In the elections the same year, he was again elected as a member of the Balochistan Assembly.

In 1993, he supported Benazir Bhutto and was elected as the member of the National Assembly. Their alliance didn’t last long either, and he initiated an opposition campaign against her.

The last time he held an office was in 1997 when he was elected as a Member of the National Assembly.

He confined himself in Dera Bugti after the murder of his son, Nawabzada Salal Bugti, whom he considered his heir, in June 1992.

On January 2, 2005, Dr Shazia Khalid, a female doctor at the Pakistan Petroleum Limited, was raped by an army captain.

Bugti demanded punishment for the rapist as the incident had happened in his area and he considered it a dishonor to Baloch society. However, the then dictator General Musharraf straightaway spoke in support of his officer and declared the captain innocent without any investigations. It was the beginning of a cold-war between Musharraf and Bugti which eventually turned into a full-fledged battle.

Musharraf’s political advisers — Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain and Mushahid Hussain – tried to resolve the issue through talks.

Sherbbaz Mazari, a seasoned politician and Bugti’s brother-in-law, told this author Shujaat and Mushahid came to his Karachi residence urging him to persuade Bugti for talks.

He said Bugti was initially reluctant because he knew the military leadership was not serious and that they want to get rid of him.

After much persuasion from Mazari, he agreed for talks. The government’s negotiators met him in Dera Bugti. But the talks failed, and Bugti claimed the negotiators had not been given any authority to resolve the issues.

After the 2005 bombing at his residence by the military, he went into hiding in the mountains. He was 86 and couldn’t walk properly because of a tumour. He seemed certain he will be assassinated.

According to Sherbaz, he called him a few days ahead of his assassination to say good-bye to him.

“It’s better to die with your spurs on, Instead of a slow death in bed, I’d rather death come to me while I’m fighting for a purpose,” he told Time Magazine in his last interview.

On August 26, 2006, his hideout was bombed, killing Bugti and dozens of his supporters. Twenty-one army soldiers were also killed in the ensuing battle.

Violent protests erupted throughout Balochistan. Government offices and machinery were burnt into ashes by angry protesters. His body, sealed in a coffin, was buried in Dera Bugti without the presence of his family.

Bugti’s murdered changed Balochistan’s politics forever. It not only gave a new impetus to the Baloch insurgency for a separate homeland, it also made Bugti the undisputed hero of the contemporary Baloch politics.

He is no longer remembered as the young man who voted for Pakistan. For the Baloch separatists, his image is that of an old but strong man on a camel leading the Baloch fighters.

Published in Balochistan Times